by Caroline McQuarrie

Last year, while watching the Nick Cave documentary ‘One more time with feeling’, I was struck by a scene where Cave is talking about his wife, Susie Bick. He speaks of how much he loves her, but ends by saying she is ultimately a mystery to him, that all women are. Cave, for all his indie credibility, is in this instance the epitome of the classical artist for whom women exist only as muse. I am in no doubt that Cave feels close to the women he has had in his life, but they are not the same as him. They are mysterious, unfathomable – other. This is the root of the male gaze, if the (male) artist cannot put himself in the position of the (female) subject, then the woman is silenced, she has no voice of her own. As women in this system, men speak for us, and about us. Yet at the same time as we are ‘mysteries’ they don’t understand us… well, you see the problem. As much fodder as this might provide the male artist, it leaves women on the outside of our own story, our own culture.

Justine Walker has found herself on the outside of her own culture in yet another way. Yet in For Sale: baby shoes, never worn Walker tells her own story, on her own terms. The work explores what the artist terms her and her partner’s ‘eight-year journey into childlessness’. We are confronted with one couple’s recurring pain. The photographic and video works see the artist engaging with the ephemera of life with small children, while missing the crucial element. We see balloons being blown up and let down, drawings made and unmade, hundreds and thousands sorted into groups of single colours, and the artist herself wearing baby pink hand knits. For Sale: baby shoes, never worn is a nuanced and layered body of work depicting a couple resolutely reclaiming their own lives after the indignity meted out to them by the medical profession. But it is perhaps most successful at describing loss. In every work, we are aware of loving actions being taking for a person who is not only missing, but who never actually existed.

In Shame triptych, one of the central works in the exhibition, we are confronted face on by the artist in a series of three photographs. Revealing only head and shoulders all she wears are a series of hand knitted, baby pink balaclavas; she sits within a woolly pink miasma. In the first image only her mouth is visible, in the second only her ear, and in the third only her eyes. The balaclava is often used in popular culture to hide one’s identity, yet here it provides no protection at all. The woman can see us, hear us and speak to us; she can watch, hear and speak her own story. There is nowhere for shame to be harboured, she is facing down the idea that it should exist at all.

In 1975 Laura Mulvey coined the term ‘the male gaze’ in her essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Particularly relevant to lens-based media, Mulvey suggested that the gaze of a camera is not neutral, rather as a medium mediated by the culture it exists within it takes on the gaze of the patriarchy it comes to represent. Feminist artists have countered this notion in two ways. Artists such as Alexis Hunter (whose photography work from the 1970s recently showed at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington) make the male gaze overt by subverting imagery we would not be surprised to see in the media, in order that we become aware of the bias. Another way to counter the male gaze is suggested by Joey Soloway in their 2016 Toronto International Film Festival keynote. They posit we create a ‘female gaze’ that doesn’t assume the male gaze as the status quo, rather utilising lens-based media in a way that puts a female/queer/trans perspective at the centre of storytelling.

I watched Soloway’s talk the same week I first saw Justine Walker’s work, and I felt immediately that I was seeing the embodiment of Soloway’s ideas. I use the term embody deliberately, Walker’s body is to the fore in this work (alongside her partner’s), as it would have been during her fertility treatment. But in her work she quietly reclaims her own strength away from the medical system she has been subsumed by for a number of years. She does not over-emote, or play to the camera, but simply uses it as a tool to record her journey through a series of actions that read as a person trying to understand her life now that it is not what she thought it would be.

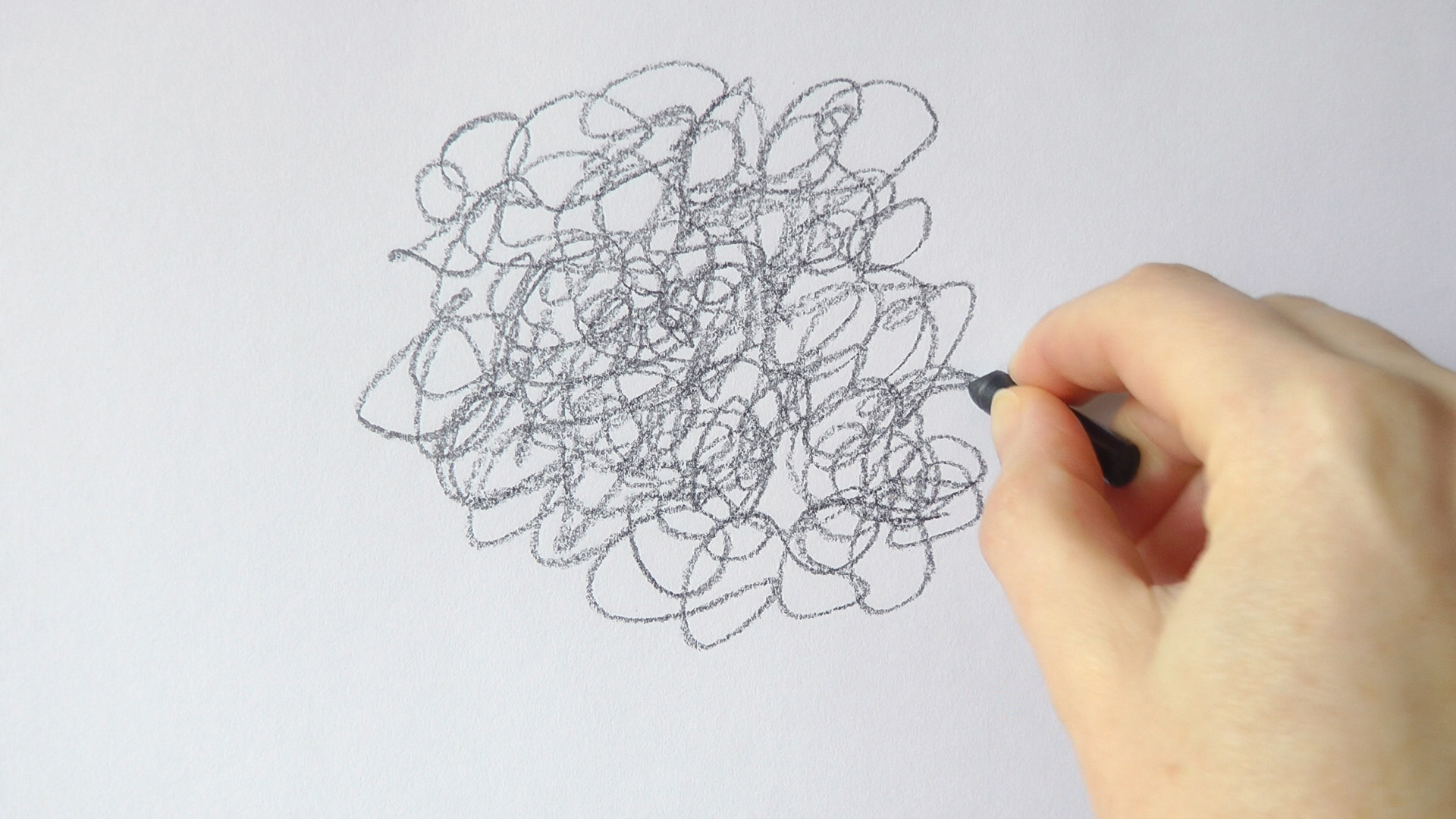

Much of the work utilises repetition, particularly the video works. We see the artist repeat action after action, putting herself through small, seemingly pointless tasks all related to a children’s birthday party. In do undo redo, we see the artist draw loose spirals all over a sheet of paper. The paper slowly fills with scribbles as her hand goes around and round, over and over. Then, when the page is full, the action is reversed and the spiralling lines disappear as though they never existed. In fertility treatment, the cycle is monthly. Every month there is a chance of success; of a life being drawn inside one’s own body, but if the treatment is not successful then every month there is also an un-drawing. Different to an erasure which needs the thing to have existed first, the un-drawing of a life necessitates accepting it never existed outside your own imagination.

Walker’s work has often required repetitious making. Employing mediums including video, drawing and embroidery, she has over a number of years explored what it means to make something slowly and methodically. A handmade object is something we expect others to value more than a mass-produced item. Even those not versed in Walter Benjamin’s theory of the ‘aura’ of the handmade object usually believe that the time and skill of the maker are admirable. This is why the readymade and photography are sometimes viewed with suspicion; they seem too easy. Walker’s work is not easily made yet this alone does not give it value. The value here is in the rich description of experience, the way this work allows us to feel what the artist felt. The repetition describes futility, numbness; it is a hopeful act with ultimately no outcome.

The only work that the artist’s own body doesn’t appear in is the video work HAPPY, in which we watch five coloured candles spelling the word HAPPY slowly melt down to nothing. As in all the works something is missing; in this case the birthday cake. These candles stand in mid-air on their sticks, and as the hot wax melts and drips it lands on a polystyrene base which it begins to melt away. The happy, colourful fun of a child’s birthday party melts into a toxic, sliding, dangerous mess. This is a party rich with melancholy, this is a party that has been ruined.

One of the most striking pieces in the suite of works is titled Little Prince. It consists of two photographs, both life sized, one a full body image of the artist herself, the other a head and shoulders image of her partner. Both stare out of their images at us with neutral expressions. Walker is wearing only a giant orange fake pregnant belly and breasts; her partner wears only a gold paper crown. These images are a haunting depiction of loss. Again, they are restrained, neither player emotes anything other than quiet dignity. But in doing so in such ridiculous circumstances we come to understand that there have been many instances in their lives where they have had to employ this dignity, even when internally they may have wanted to rail against the injustice of their situation. So they have put on their costumes, set up a party, and invited us along. They are the poignant and heart-breaking welcoming committee to the party no one wants to go to.

Caroline McQuarrie is an artist whose practice explores the expanded notion of home, whether located in domestic space a community or the land, through photography, video and craft-based works. She is a Senior Lecturer in Photography at Whiti o Rehua School of Art, Massey University, New Zealand. www.carolinemcquarrie.com